Books of herbal remedies, on the other hand, were widely distributed and not secret. We do have examples of information being made secret, but it’s military information or political information, and it’s 100 or 150 years later. But that strikes me rather more as a Dan Brown scenario than something that might have actually happened. One theory that’s come up, which I’m not sure I buy into, is that this was witchcraft or it was a manuscript that contained information that the Catholic Church didn’t want to get out. So, why do people people encipher things in general? Either to to hide it from people who shouldn’t see it, or to create some sort of in-group solidarity type of thing. I think people in the medieval period probably acted from similar sorts of motivations to people these days. Why would someone in those days create a ciphered manuscript? Of course, it could be a copy of even earlier material, just as we have modern paperbacks of Shakespeare but the plays themselves go back hundreds of years.

The type of ink is typical of what was used in that time period, and the clothing of the figures in the illustrations and so on are all consistent with that time period. We get that from the carbon dating of the parchment, which puts it between 14. I’m pretty comfortable saying this is an early 15th century object. Is there any chance he created the manuscript himself? He received a number of manuscripts from the Jesuit archives, and it’s not quite clear whether they knew that this manuscript was part of it, or whether the person who was selling the manuscript had the authority to do so. Partly that, and also it’s not quite clear whether he obtained the manuscript totally above board. Was he trying to increase the price he could get by creating an air of mystery around it? Or what was he up to? Wilfrid Voynich, shown here in a photograph taken around 1899, was never completely forthcoming about how he acquired the mysterious manuscript that bears his name. He said he found it in a castle, but that seems like he was trying to be unclear about where he got it. He was never clear in his lifetime about where it came from. Voynich himself shrouded the manuscript in mystery. And from there it went to the library of the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher, and presumably stayed there until it ended up in a Jesuit archives outside Rome, where Wilfrid Voynich found it in 1911 or 1912. We know that the manuscript was in Prague in the early 1600s. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.ĭo we know where the manuscript came from or who created it? She spoke with Knowable about some of their insights.

#What is the voynich manuscript software#

Seeing the manuscript in person got Bowern thinking: Even though her main research focus is on documenting endangered Indigenous languages in Australia (where she’s from), perhaps some of the statistical methods, software and approaches that she and other linguists use to study and compare languages could be used to study the Voynich manuscript.īowern created and taught an undergraduate class to explore the possibilities, which she and post-doctoral researcher Luke Lindemann describe in a recent paper in the Annual Review of Linguistics.

#What is the voynich manuscript tv#

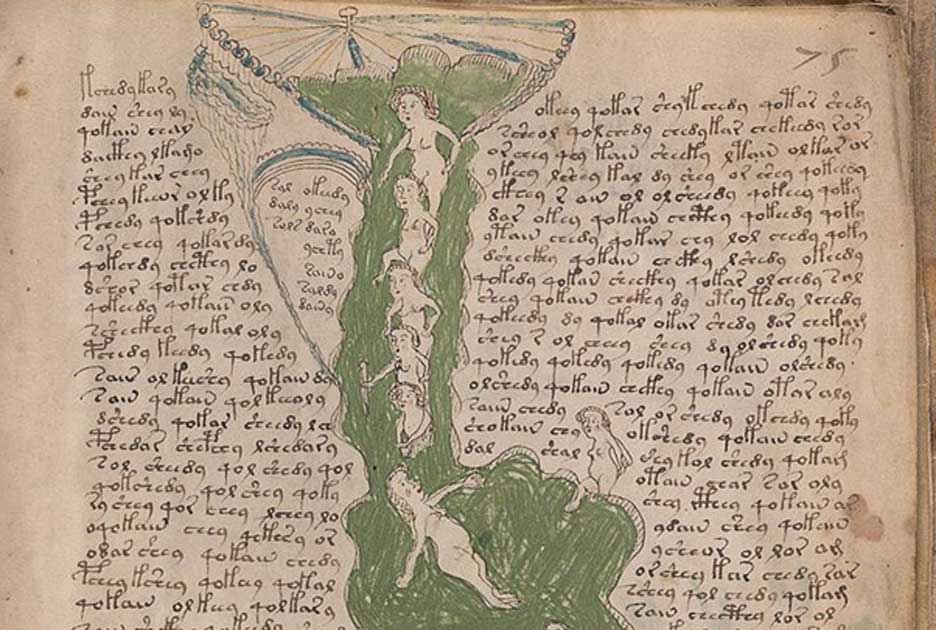

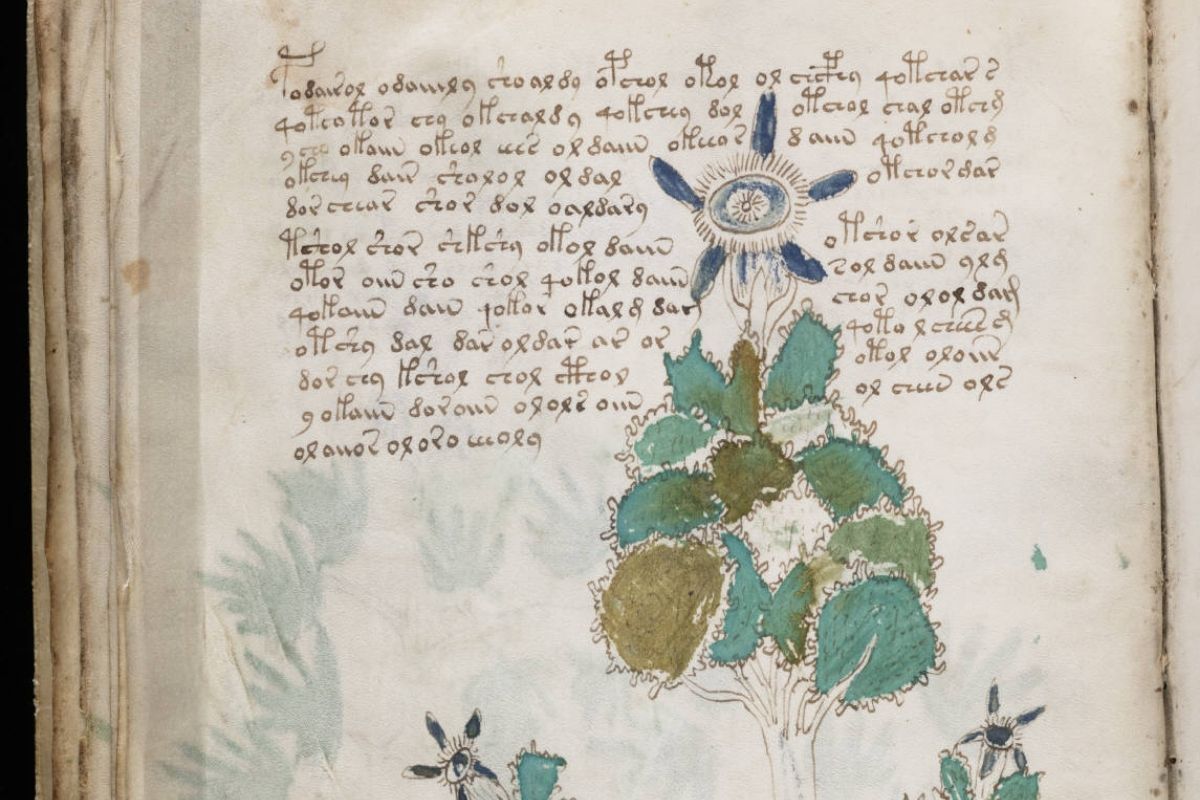

The mystery surrounding the Voynich manuscript has inspired novels, cameo appearances in popular TV shows and video games, and even a symphony - which debuted at Yale in 2017, along with an exhibit Bowern attended with a couple of her students. A “pharmaceutical” section depicts what may be herbal remedies - plant roots alongside medicine bottles - and a fifth section, unillustrated, has blocks of text demarcated with little stars. The section with the bathing nymphs is often called the balneological section, a reference to the science of baths and bathing. The astrological section includes zodiac charts and depictions of the sun and moon. The section on plants is the longest, making up just over half of the manuscript. It appears to have five main sections, she says. “It’s surprisingly small, a bit bigger than a paperback,” says Yale linguist Claire Bowern. The manuscript now resides in the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University. None of these claims has gained widespread acceptance.

In 2018, a pair of researchers, citing the apparent similarity of some of the manuscript’s plant illustrations to the flora of Central America, claimed that the manuscript was produced by the ancient Aztecs. Others have variously claimed that the underlying language is Latin, or one of the Romance languages or Hebrew. Some scholars have argued that the text is gibberish, the document an elaborate hoax. The manuscript takes its name from Wilfrid Voynich, the Polish-born antiquarian who acquired and publicized it in the early 20th century. CREDIT: JAMES PROVOST (CC BY-ND) Linguist Claire Bowern

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)